One of the besetting difficulties surrounding discussions of sexuality is terminology. Many of us are simply not on the same page when it comes to the meaning of the terms we use to frame the discussion. Also, many of the terms we use are loaded with baggage from secular theory that does more to confuse than to illuminate.

One of the besetting difficulties surrounding discussions of sexuality is terminology. Many of us are simply not on the same page when it comes to the meaning of the terms we use to frame the discussion. Also, many of the terms we use are loaded with baggage from secular theory that does more to confuse than to illuminate.

I’ve been thinking recently about one of these terms and how its current usage does indeed confuse rather than clarify. That term is attraction. Many people who write about sexuality tend to use “attraction” and “desire” as synonyms. Thus to say that someone experiences “same-sex attraction” is just another way of saying that they experience “same-sex desire.” I think this usage is a demonstrable fact in both theological and non-theological literature. I give a number of examples in my book, but I will provide one here to illustrate the point. In their book Sexuality and Sex Therapy (InterVarsity, 2014), Mark Yarhouse and Erica Tan write this (p. 296):

When we discuss sexual orientation . . . we are referring to what is often thought to be a more enduring pattern of attraction to another based on one’s sexual desire. . . . Orientation is often discussed in our cultural context as heterosexual (sexual desire as attraction to the opposite sex), homosexual (to the same sex) and bisexual (to both sexes). [underline mine]

Notice what Yarhouse and Tan have done in this excerpt. Not only have they used “attraction” and “desire” as synonyms, they are actually defining “attraction” in terms of “desire.” My observation is simply that many people writing in this area (including yours truly) have used these two terms as virtual synonyms.

But it is on this point that I want to raise a question. And my point may seem overly pedantic at first, but if you hang with me perhaps you’ll see the substantive concern I’m raising.

I detect a bit of moral ambiguity in the connotation of the term “attraction,” especially among Christians trying to distinguish what is culpable (lust, desire for immorality, etc.) from what they argue may not be culpable (same-sex attraction, sexual attraction more generally). There are some who might concede that desire for immoral activity is sinful. Those same people, however, might also argue that the mere experience of an attraction to this or that person is just a morally indifferent description of someone’s experience.

Where does this ambiguity come from? I think the ambiguity is found in part in the connotations of the terms—connotations that are different and that seem to persist independently from their general use as synonyms.

I know that words gain their meanings through usage in context. I get it. My concern is that these connotative meanings may be shaping not only our vocabulary but also our thinking on these subjects. My thesis is this: I believe the term “desire” to be superior to the language of “attraction” in our moral vocabulary. My reasons are twofold:

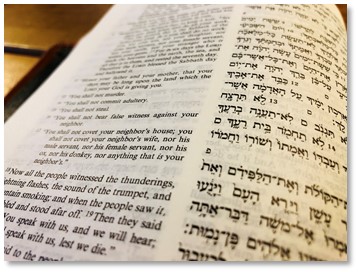

1. The Vocabulary of Scripture

The first and most important reason to prefer “desire” over “attraction” is that “desire” is the moral vocabulary of scripture, not “attraction.” This is true in both the Hebrew of the tenth commandment and the Greek translation of this term in the New Testament.

The Hebrew term for “desire” in the tenth commandment is khamad (Exod. 20:17). In its wider usage, such desire is either good or evil based on its object. If someone desires a good thing, then the desire is good (e.g., Psalm 19:10). If someone desires an evil thing, then the desire itself is evil (e.g., Gen. 3:6). Likewise, the key New Testament word-group for “desire” is epithumia/epithumeo and works in a similar way. If someone desires a good thing, then the desire itself is good (e.g., 1 Tim. 3:1; Matt. 13:17). If someone desires an evil thing, then the desire itself is evil (e.g., 1 Cor. 10:6). This holds for all human desire, including but not exclusive to sexual desire (e.g., Prov. 6:25; Matt. 5:28).

The important thing to note for our purposes is that the Hebrew and Greek terms describe the craving/longing/wanting of an agent. In other words, desire is something someone does. It’s not something that is done to them. As we shall see, the term “attraction” does not have that same clarity.

2. The Ambiguous Agency of Attraction

The second reason for preferring “desire” over “attraction” is that “attraction” does not express what an agent does but what is done to an agent. “Desire” expresses the agency of the subject. The same is not quite true with “attraction” and its cognates. Consider the difference between the following two sentences:

“I experience desire for good art.”

“I experience attraction to good art.”

As written, the nouns attraction and desire are arguably synonymous. But look what happens if you transform those terms into the active verbs they are based on:

“I desire good art.”

“Good art attracts me.”

This little transformation reveals what is at least a connotative difference between the nouns desire and attraction. Desire is what someone does while attraction is done to someone.

The bottom line is this. Attraction language subtly offloads agency from the one who experiences attraction to the person or thing attracting him. This is an important difference, and it is why “attraction” confuses more than clarifies in our moral vocabulary concerning sexuality. Consider the following expressions:

“I experience desire for the same-sex.”

“I experience same-sex attraction.”

Now let’s transform the nouns to verbs to reveal who the implied agents and objects are:

“I desire the same-sex.”

“The same-sex attracts me.”

My point here is not merely grammatical but moral. The phrase same-sex attraction is not the clearest way to express the moral agency that someone has in their sexual feelings, but desire is. The Bible’s language of desire does not have the shortcomings of attraction. Desire clearly expresses what a person longs or craves for. It allows the potential for culpability in those longings without offloading moral agency onto someone or something else.

Bottom Line

Again, I am not trying to be pedantic here. I’m simply trying to clarify something that I have often found to be confusing among those who write and speak about sexuality. As I mentioned at the beginning, many people use same-sex attraction and same-sex desire as synonyms. But they actually aren’t quite synonyms.

I am not trying to reduce the debates we are having about the morality of same-sex attraction to a matter of linguistics. I know that there are substantive differences here. I’m merely suggesting that the language of attraction may be concealing some of those differences by concealing the moral agency in our sexual feelings. The Bible’s language of desire does not suffer from this limitation. If all sides were to adopt the Bible’s language in our current debates, it would likely help to clarify what is now so sadly confused. The Bible describes our sexual feelings in terms of desire not in terms of attraction. We ought to do the same.