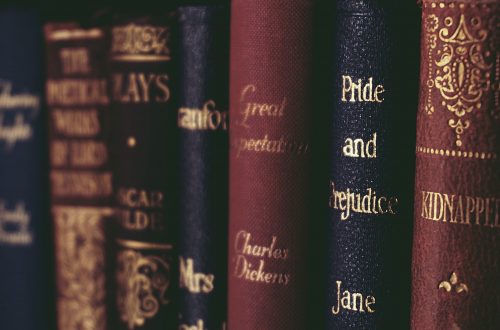

Craig L. Blomberg, Making Sense of the New Testament: Three Crucial Questions (Baker: Grand Rapids, 2004). ISBN: 0801027470. $14.99.

Craig Blomberg’s Making Sense of the New Testament is published as a companion volume to Tremper Longman’s 1998 book, Making Sense of the Old Testament: Three Crucial Questions. In the current volume, Blomberg sets out to identify “three crucial questions†that must be answered by anyone who wishes to consider the truth-claims of the New Testament. In chapter 1, he sets out to answer the question of whether the New Testament presents a reliable historical portrait of Jesus. Here he takes up the old question of whether the Christ of history resembles the Christ of the scriptures. Blomberg concludes that the historicity of the Gospels and Acts is confirmed by sound evidence and that accepting their historical claims does not require a leap of faith. Blomberg does a good job of taking the reader step-by-step through the evidence, and in the end produces a very convincing apologetic for the veracity of the Gospels and Acts.

In chapter 2, Blomberg takes up the controversial question whether Paul was the true founder of Christianity. He queries whether the teaching of Jesus can be reconciled with the teaching of the great apostle to the Gentiles: “Was Paul, in fact, the second founder, or perhaps even the true founder of Christianity as it has developed down the centuries?†(p. 15). In this section, Blomberg responds to the skeptical charge that Paul’s letters reveal a radical revision of the teachings of the historical Jesus. Blomberg does well to point out that Paul is aware of the Jesus traditions that were current in his day and that some of these traditions appear in his letters. In 1 Corinthians 11:23-25, for instance, Paul makes use of a tradition that was handed down to him by word of mouth. This tradition looks remarkably similar to Luke’s version of the Jesus’ words at the Last Supper (Luke 22:19-20). Paul and Luke’s use of a common oral tradition shows the antiquity of Paul’s theology of atonement and that he was concerned with the historical Jesus. Blomberg wrestles with other texts in Paul that allude directly or indirectly to Jesus’ teachings. Blomberg says that, “Theological distinctives between the two men remain, and the differing purposes of the Gospels and the Epistles must be taken into account†(p. 106). Thus, there is more evidence of continuity between Jesus and Paul than is commonly acknowledged by New Testament scholars, and the points of discontinuity can be explained by the different purposes of Paul the letter writer and the evangelists who wrote the Gospels.

In chapter 3, Blomberg considers how the New Testament applies to the modern day. He explores the various principles that govern the interpretation of the New Testament’s diverse literary forms. These include (1) determining the original application intended by the author of the passage, (2) evaluating the level of specificity of those applications to see if they should be or can be transferred across time and space to other audiences, (3) if they cannot be transferred, identifying broader cross-cultural principles that the specific elements of the text reflect, and (4) finding appropriate contemporary applications that embody those principles (p. 108). He then works out these principles in relation to the different sections of the New Testament canon: the Gospels, Acts, Paul’s letters, Hebrews and General Epistles, and the Revelation. The principles that Blomberg elucidates can provide a good starting-point for developing legitimate implications out of the author’s original meaning. One notices, however, that it is still unclear how one is to know when it is appropriate to move beyond the intention of the biblical author in applying the scripture. For example, on page 140 Blomberg says that the interpreter needs to “recognize that Paul lays down principles which could not be fully implemented in his world but which challenge later Christians to move even further in the directions he was already heading†(emphasis mine). This “further†idea sounds remarkably similar to William Webb’s “redemptive movement hermeneutic,†to which Blomberg refers in an extended footnote on pages 172-173. Webb’s hermeneutic appears to the present reviewer to be highly unstable and, in Webb’s application of it, favorable to an egalitarian reading of Paul.

In sum, Blomberg has produced a handy little primer on some of the basic questions that face the reader of the New Testament. There is not much new here for specialists in the field, but this book will be useful for beginning students of the New Testament at both the college and graduate levels. It is also useful as an apologetic tool for anyone who might be interested in evidence concerning the historical claims of the New Testament.