If last summer’s trinity debate did anything, it raised awareness among evangelicals about the primary importance of eternal generation in distinguishing the persons of the trinity. As I have written previously, it also highlighted the fact that the Nicene Fathers were interpreting scripture when they confessed Jesus to be the “only-begotten” son of God.

As we approach the one year anniversary of the beginning of last summer’s trinity debate, I thought it might be worth noting one small way that the debate impacted the liturgy of the church where I serve as a pastor. Our church follows a regular liturgical order, which includes a recitation of the Apostles’ Creed before receiving communion. We do this every Sunday, week in and week out. The only exception is that once a quarter we recite our church covenant in place of the Creed. That has been our longstanding practice, but several months ago we began confessing Jesus as “only-begotten” in the Apostles’ Creed.

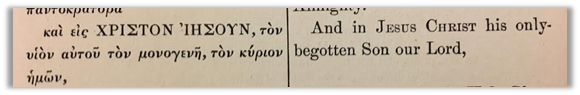

Why weren’t we confessing “only-begotten” before the trinity debate? The short answer is that we were relying on English translations of the Creed, many of which render the Greek term MONOGENES as “only” or that follow a Latin version that has unicum (“only”) rather than unigenitum (“only-begotten”). In any case, the Greek form is generally regarded as the oldest form of the Creed and may even be as old as the second century.1 And the Greek form (which I hadn’t read before the Trinity debate) clearly has MONOGENES.

For that reason, we have included “only-begotten” in our weekly confession of the Apostles’ Creed. It is the language of the oldest form of the Apostles’ Creed. It is the language of the Nicene Creed. And most importantly, it is the language of scripture itself (John 1:14, 18; 3:16; 1 John 4:9). It is the universal confession of the Christian church. I hope our English translations of the Creed in public worship will reflect that. The recitation in our church now does. Perhaps it will in yours too.

_________________________

1 Philip Schaff, The Creeds of Christendom, with a History and Critical Notes: The History of Creeds, vol. 1 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1878), 19.