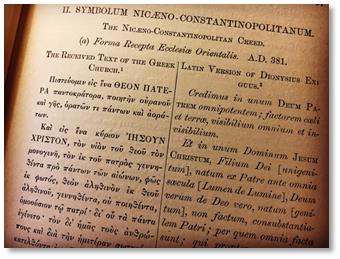

Last summer, I did something that I had never taken the time to do before. I read the Nicene Creed in Greek. Of course I was very familiar with the English version of the Creed before then, but not so much the Greek. One thing that is clear in the Greek is that the Nicene fathers were interpreting scriptural terms in saying that Jesus is the “only begotten” (MONOGENES) and “begotten not made” (GENNAO). These terms derive from John’s writings, and the Creed clearly interprets MONOGENES to denote “generation” or “begottenness.”

That the Son is “begotten not made” and “begotten before all ages” means that the Son’s “only-begottenness” is eternal. Thus the doctrine of eternal generation emerges in the Creed not only as the church’s confession but also as an interpretation of specific biblical texts (John 1:14; 1:18; 3:16; 1 John 4:9). To be sure, the doctrine of eternal generation has a broad biblical basis and does not rely solely on MONOGENES. Nevertheless, the Nicene Fathers feature MONOGENES in the Creed as an exegetical linchpin for the doctrine.

After reading the Creed in Greek, it immediately became clear to me that the Nicene Fathers’s interpretation of MONOGENES is in direct conflict with a near consensus among modern New Testament scholars. Since about the middle of the 20th century, it has become commonplace among New Testament scholars to reject the Nicene Fathers’s interpretation of this term and to say that MONOGENES means “only” or “unique” and thereby to remove this term as an exegetical proof for eternal generation. I could multiply examples here, but I will just offer a sampling:

“In the preface of the New King James Bible, we are told that the ‘literal’ meaning of MONOGENES… is ‘only begotten’… All of this is linguistic nonsense.”

–D. A. Carson, Exegetical Fallacies, p. 28 (see also pp. 30-31)

“‘Only-begotten’ fails the etymology test, as it would require a different word… MONOGENES derives instead from a different root, GENOS, leading to the meaning ‘one of a kind.'”

–Craig Keener, The Gospel of John, Vol. 1, pp. 412-13

“We should not read too much into ‘only begotten’… To English ears this sounds like a metaphysical relationship, but the Greek term means no more than ‘only,’ ‘unique.'”

–Leon Morris, The Gospel according to John, p. 93

“The emphasis is not that Jesus was ‘begotten’ of God, but that God had only one Son, and this ‘one and only’ Son he sent into the world…”

–Colin Kruse, The Letters of John, p. 159

“There is little Greek justification for the translation of MONOGENES as ‘only begotten.'”

–Raymond Brown, The Gospel according to John (i-xii), p. 13

“MONOGENES therefore means not ‘only begotten,’ but ‘one-of-a-kind’ son…”

–Andreas Kostenberger, John, p. 43

As I said, I could go on with a list of examples as long as my arm. New Testament scholars routinely dismiss the “only begotten” interpretation of MONOGENES. To be clear, this does not mean that they are rejecting the doctrine of eternal generation per se. It means that they are rejecting a scriptural basis for it that is cited in the Creed. The question is why has this dismissal become so commonplace? Many of the authors listed above cite the same source for their arguments—a single journal article that appeared in 1953 in the Journal of Biblical Literature:

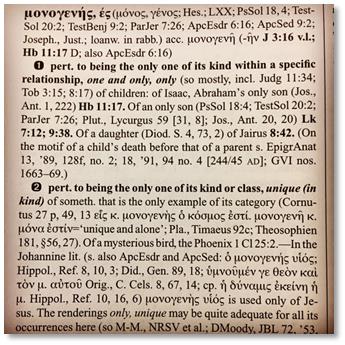

Moody’s article defends the RSV’s translation of MONOGENES, arguing that “only begotten” is an etymological, linguistic, and historical error. He certainly was not the first one to have made this case, but his arguments in particular seem to have influenced at least two generations of New Testament scholarship. I think this is due in no small part to the fact that Moody’s article is the first one cited in BDAG’s entry on MONOGENES (BDAG is the most important and authoritative lexicon of New Testament words; see right). Anyone looking to BDAG for a definition of MONOGENES is going to be confronted with the non-generative interpretation of the term that is reflected in Moody’s article.

Moody’s article defends the RSV’s translation of MONOGENES, arguing that “only begotten” is an etymological, linguistic, and historical error. He certainly was not the first one to have made this case, but his arguments in particular seem to have influenced at least two generations of New Testament scholarship. I think this is due in no small part to the fact that Moody’s article is the first one cited in BDAG’s entry on MONOGENES (BDAG is the most important and authoritative lexicon of New Testament words; see right). Anyone looking to BDAG for a definition of MONOGENES is going to be confronted with the non-generative interpretation of the term that is reflected in Moody’s article.

(One interesting historical note: Dale Moody was a professor at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary during its former liberal era. Moody’s work is apparently based on Francis Warden’s Ph.D. dissertation written at SBTS in 1938. Over the summer, I went to SBTS’s library and found the dissertation. It is still unpublished, but a summary of Warden’s conclusions appeared in April of 1953 in the journal Review & Expositor. Moody’s article appeared later that same year in December in the Journal of Biblical Literature.)

Many NT scholars view Moody’s article as the definitive word on MONOGENES, but I believe that Moody was wrong—really wrong. And here’s why.

1. Moody claims the suffix –GENES means “kind” without any notion of generation.

Moody is correct that the Greek suffix –GENES derives from the word GENOS. But Moody is wrong about the semantic range of GENOS and the suffix derived from it. In some contexts GENOS means “kind,” but in other contexts it means “offspring.” In fact, in John’s one use of the term GENOS, it clearly refers to “offspring” or “one that is begotten from another” (Revelation 22:16). “Offspring” is the only attested meaning for this term in John’s writings! Moody is also wrong about the semantic range of the –GENES suffix. There are many examples of this suffix that indicate “begottenness.” For example, OIKOGENES means “home-born” (Gen. 15:3 LXX). Paul uses the term EUGENES to mean “well-born” (1 Cor. 1:26). Again, Moody has misconstrued both the meaning of GENOS and the suffix derived from it.

2. Moody says that if John had meant “only-begotten” he would have used the term MONOGENNETOS.

Why does Moody claim that John would have used the term MONOGENNETOS, not MONOGENES, if he had meant “only begotten”? Because the former is derived from the verb GENNAO, which everyone agrees denotes generation. We’ve already seen that Moody is mistaken about GENOS, but he’s also mistaken about MONOGENNETOS. The term MONOGENNETOS does not appear to be attested in ancient Greek literature before the second century (it does not appear in Liddell-Scott’s lexicon). If John were to have used the term, he would have to have been the one to coin it. But why would John coin a new term when MONOGENES was ready at hand? This is a term, after all, that means “only-begotten” in numerous texts across ancient Greek literature (according to Lee Irons’s recent research in which he has located 60+ examples of MONOGENES in non-biblical Greek before the second century).

3. Moody argues that MONOGENES in Hebrews 11:17 cannot possibly mean “only-begotten.”

Moody cites Hebrews 11:17 as decisive evidence against the “only-begotten” interpretation of MONOGENES. Hebrews 11:17 says that “Abraham… was offering up his MONOGENES son.” Moody says that because Abraham had other children (e.g., Ishmael), the term can’t mean that Isaac was his “only begotten.” MONOGENES must indicate that Isaac was his “unique” son. But this is mistaken as well. The writer of Hebrews is specifically pointing out that Isaac is “uniquely begotten.” The author is showing incredible sensitivity to the wider context of Genesis in which Abraham had once questioned whether his heir would come from his own body (Gen. 15:2-4) and whether that heir from his own body would be Ishmael (Gen. 17:18, 21). “Begotten” addresses the first question, and “uniquely” addresses the second. In other words, the idea of “begottenness” is necessary in this context. Moody has this completely backwards.

4. Moody’s linguistic arguments are not sensitive to the context of John’s use of the term.

In every instance that John uses the term MONOGENES, it follows a passage/context in which he uses the term GENNAO to refer to the “new birth”—every single instance (see John 1:14, 18; 3:16, 18; 1 John 4:9). That is no accident. John is intentionally drawing a distinction between the new birth that we experience and the Son’s unique begottenness from the Father. John seems to be saying that while Christians have been “begotten” by the Holy Spirit, Jesus is the “uniquely begotten” Son of God. His “begottenness” is different from ours and indeed utterly without parallel.

As I mentioned in a previous post, Lee Irons has undertaken a research project that has made a decisive case for “only-begotten” as the meaning of MONOGENES in John’s writings. But before I ever saw that research, the above lines of argument are what convinced me that Moody’s arguments do not hold up to the evidence. For that reason, I think that scholars who have based their opinion of MONOGENES on the arguments of Dale Moody or on the entry in BDAG need to reevaluate their position. Those who view the doctrine of eternal generation as speculative and as having little biblical warrant need to reevaluate as well.

It turns out that the Nicene Fathers knew Greek really well—probably better than any of us reading the New Testament today. I think that the interplay between MONOGENES and GENNAO in the Creed shows that the Nicene Fathers noticed the interplay of those same terms in John’s writings. They were interpreting the Greek Bible in the Creed, and they were and are right. Jesus is the uniquely generated Son of God, begotten, not made, before all ages.