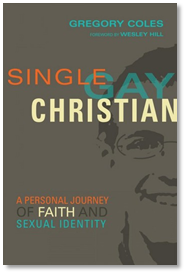

I just finished reading Gregory Coles’ moving memoir Single Gay Christian: A Personal Journey of Faith and Sexual Identity (IVP, 2017). In many ways, there is much to admire about this book. Coles is a great writer and has put together a real page-turner. This is not a boring book. Coles’ honesty and vulnerability come through in just about every page. Coles is telling his own story—warts and all—and he’s gut-wrenchingly honest about his emerging awareness of himself as a same-sex attracted man.

I just finished reading Gregory Coles’ moving memoir Single Gay Christian: A Personal Journey of Faith and Sexual Identity (IVP, 2017). In many ways, there is much to admire about this book. Coles is a great writer and has put together a real page-turner. This is not a boring book. Coles’ honesty and vulnerability come through in just about every page. Coles is telling his own story—warts and all—and he’s gut-wrenchingly honest about his emerging awareness of himself as a same-sex attracted man.

Coles’s story is a very human story, and just about anyone (same-sex attracted or not) can resonate with the humor and the pathos that he narrates. By the end of it, you feel like you know the man. And this is a man who embraces the Bible’s prohibitions on same-sex immorality. Because of that, he has dedicated himself to a life of celibacy out of faithfulness to Christ. As hard as it is, Coles has concluded that faithfulness to Jesus on this point is more important than pursuing a gay relationship.

So there is much that I resonate with in Coles’s story. In the end, however, I share the same concerns about the book that Rachel Gilson expressed in her review at TGC.

First, this book falls squarely within the celibate gay identity genre, in which the author rejects gay sexual behavior and gay marriage but embraces a gay identity. Coles argues that being gay is “central to my identity” (p. 37). He resists referring to himself simply as one who experiences same-sex attraction. Coles believes that describing himself as same-sex attracted might imply that the experience is merely a “phase” he is going through (p. 63). He maintains that being gay is something that defines him at the core of his being. His sexual attractions are not just how he is but who he is. Coles writes:

I began to realize that my sexual orientation was an inextricable part of the bigger story God was telling over my life. My interests, my passions, my abilities, my temperament, my calling—there was no way to sever those things completely from the gay desires and mannerisms and attitudes that had developed alongside them. For the first time in my life, I felt free to celebrate the beautiful mess I had become (p. 43).

Coles not only argues that homosexuality is core to his identity, he even suggests that it may be a part of God’s good design.

Is it too dangerous, too unorthodox, to believe that I am uniquely designed to reflect the glory of God? That my orientation, before the fall, was meant to be a gift in appreciating the beauty of my own sex as I celebrated the friendship of the opposite sex? That perhaps within God’s flawless original design there might have been eunuchs, people called to lives of holy singleness?

We in the church recoil from the word gay, from the very notion of same-sex orientation, because we know what it looks like only outside of Eden, where everything has gone wrong. But what if there’s goodness hiding within the ruins? What if the calling to gay Christian celibacy is more than just a failure of straightness? What if God dreamed it for me, wove it into the fabric of my being as he knit be together and sang life into me? (pp. 46-47)

Coles suggests that same-sex orientation may be a part of God’s original creation design and that homosexual orientation within Eden is an ideal that exceeds that which people experience outside of Eden.

I do not know how to reconcile this perspective with scripture or with the natural law. Same-sex orientation is not simply a “creational variance” (as Nicholas Wolterstorff has described it). Scripture teaches explicitly that homosexual desire and behavior are “against nature”—meaning against God’s original creation design (Rom. 1:26-27). Nor can I reconcile this perspective with what Coles says elsewhere about same-sex orientation being a “thorn in the flesh,” which suggests that same-sex orientation is not a part of God’s original design. Which is it? A thorn in the flesh or something God “dreamed” for people as a part of his original design?

The answer to this question is not clear in this book, and that omission has enormous pastoral implications in the lives of people who experience same-sex attraction. Should they embrace their attraction as a “gift” from God that is a part of his original design for them? Or should they recognize those attractions as a part of what has gone wrong in creation? Should they try to find something holy in those desires, or should they flee from them? I am concerned that readers will not find a clear answer in this book. And there can be soul-crushing consequences for answering those questions incorrectly.

Second, Coles says that the Bible’s teaching on homosexuality and same-sex marriage is not as clear as conservative Christians suggest. After studying the issue and really digging into it for himself, he concludes that the Bible does not support same-sex marriage or homosexual behavior. Nevertheless, because the Bible is less straightforward on the matter than he previously was led to believe, he ends up treating the issue as one that faithful Christians may agree to disagree about. He writes,

The Bible’s treatment of homosexuality was complicated. More complicated than the well-meaning conservative preachers and ex-gay ministers were ready to admit. But the fact that it was complicated didn’t make every interpretation equally valid. There was still a best way of reading the text, still a truth that deserved to be pursued.

And when I pursued it, I got the answer I feared, not the answer I wanted. More and more, I found myself believing the Bible’s call to me was a call to self-denial through celibacy (pp. 36-37).

Coles goes on to explain that even though he embraced a conservative stance on the issue, the Bible’s lack of clarity continued to affect his views.

I was still sympathetic to the revisionist argument that affirmed the possibility of same-sex marriage. Part of me still wanted to believe it, and I understood at the most visceral level why some sincere Christians might choose to adopt this view (p. 37).

Even though Coles disagrees with those living in homosexual relationships, he nevertheless identifies some who do as “sincere Christians.” Near the end of the book, he elaborates even further:

And yet if I’m honest, there are issues I consider more theologically straightforward than gay marriage that sincere Christians have disagreed on for centuries. Limited atonement? “Once saved always saved”? Infant baptism?… If we can’t share pews with people whose understanding of God differs from ours, we’ll spend our whole lives worshiping alone (pp. 108-109).

Coles says that he does not wish to be the judge on such matters and says that judging other people’s hearts is “none of my business” (p. 110). He adds that the issue falls under the warning of Romans 14:4: “Who are you to judge someone else’s servant? To their own master, servants stand or fall” (p. 110).

Coles seems to equate differences about homosexual immorality with differences that Christians have about second order doctrines. But how can homosexual immorality be treated in this way when the Bible says that those who commit such deeds do not inherit the kingdom of God (1 Cor. 6:9-11)? In scripture, sexual immorality is not compatible with following Christ (Eph. 5:5-6). How then can “sincere Christians” engage in such activity and still be considered followers of Christ? Coles does not seriously engage this question. He simply says that “sincere Christians” may come to different conclusions.

So much of the evangelical conversation on these issues has been colonized by secular identity theories. Those theories are premised on an unbiblical anthropology which defines human identity as “what I feel myself to be” rather than “what God designed me to be.” If there is to be a recovery and renewal of Christian conscience on sexuality issues, secular identity theories must give way to God’s design as revealed in nature and scripture. Gay identity proposals, in my view, are not bringing us any closer to that renewal.

I really enjoyed getting to know Coles’s story. I can’t help but admire his continuing commitment to celibacy and traditional marriage. I want to cheer him on in that and say “amen.” Still, I am concerned that the celibate gay identity perspective he represents is not biblically faithful or pastorally helpful. And the issue is important enough to flag in a review like this one. Evangelicals need to think their way through to biblical clarity on sexuality and gender issues, but the celibate gay identity view is muddying the waters.